Keeping and Breeding the dwarf cuttlefish Sepia bandensis

Originally published in Advanced Aquarist and and later on TONMO and TheCephalopodPage.

Why Cuttlesfish?

I may be biased. Ok, I am completely biased. I think cuttlefish may very well be the coolest animals on the planet. They maneuver around their tank like hummingbirds, vertically, horizontally, their fin appearing blurred like bird wings. As they fly about they flash amazing color changes, creating patterns that pulse and shift and shimmer on the canvas of their skin. They are master predators, stalking their prey with cunning and attacking with accuracy, speed and skill. Over time, they learn to recognize and respond to you, and will often greet you when you walk into the room (or maybe they just know you bring the food). They are smart, beautiful and unusual, and unlike certain other eight-armed Cephalopods, they don't try to escape from your aquarium.

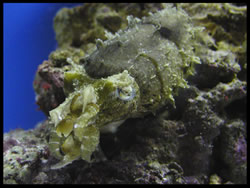

Photo 1: Adult Sepia bandensis 'begging' for food. Head/body length about 4 inches. Photo, Richard Ross

My History

My infatuation with cuttlefish started when I was a kid. To me, they just looked like extraterrestrials, and they seemed so smart that I wanted to know more about them. I read about them, made expeditions to public aquariums to see them, and watched any program on cephalopods, hoping to catch a glimpse of these fascinating creatures. Through it all, I hoped for a cuttlefish of my own, but none ever seemed to reach the market. I kept seeing shows on research being done on cuttlefish, but no research station breeding them is able sell them to individuals (please don't bother them by asking!).

Twenty years later, after I had become proficient at reefkeeping, I started noticing cuttlefish appearing at local fish stores about once a year. However, they always seemed unhealthy and I was reluctant to try my hand with less-than-robust animals. Finally, in 2003 (I waited a long time!) two cuttles came into a LFS that I am friendly with. When both cuttles eagerly ate, I decided to take a chance. Two years later, I converted an entire room in my house to cuttle fish breeding and husbandry. For more information on my set up, and cuttlefish video (I am quite proud of the videos) please check out www.DaisyHillCuttleFarm.com .

Keeping cephalopods, and especially cuttlefish, in home aquariums is still in its infancy, so I thought I would write an article with all the information I would have wanted when I started keeping them. This is not to say that there isn't info out there - The Octopus News Magazine Online (www.TONMO.com ), which recently held its first cephalopod convention in Monterey Ca, and The Cephalopod Page, currently celebrating its 10 year anniversary (http://www.thecephalopodpage.org), both have much good information and I use them often; this article is intended to supplement those resources. My hope is that one day, cultured cuttlefish will be commonplace in the aquarium hobby, and I hope that this article will entice people to not only keep them as pets, but will inspire people to breed them as well.

Most of the information available on cuttlefish concerns itself with Sepia officinalis, mainly because they have been raised and used widely for research in the scientific research community. Another reason there is hobby-side information on S. officinalis is because they have been relatively easy for European hobbyists to obtain.

There is sporadic importation of other species of cuttlefish into the USA, the most common of these imports is Sepia bandensis. There isn't much information on keeping S. bandensis because they have not been studied very much in the scientific arena, and they have rarely survived for very long in the home aquarium.

I believe that S. bandensis, provided captive bred/raised animals are available, are well suited to life in the home aquarium. It is important to note that I am not a cuttlefish 'guru' and that I expect that some of my ideas regarding cuttlefish husbandry will change as more people start keeping these animals successfully. There is much we don't know, and it is my hope that my experience and ideas will inspire more people to work with these amazing animals, that our knowledge of their husbandry needs grows rapidly, and that captive raised S. bandensis become commonplace in the near future.

Nuts and bolts

Definitions

Just what the origin of the word 'cuttlefish' is has not been pinned down, but according to cephalopod researcher John W Forsythe, "The name Cuttlefish originally came about as the best guess of how to spell or pronounce the Dutch or perhaps Norwegian name for these beasts. It is derived from something like 'codele-fische' or 'kodle-fische'. In German today, cuttlefish and squids are called tintenfische, meaning 'ink-fish'. I've been told that the term fische actually refers to any creature that lives in the sea or are caught in nets when fishing, not just fishes. Anyway, that's what I understand the derivation of name to be."1

The cuttlefish isn't a fish at all - it is a cephalopod. Cephalopod researcher Dr. James Wood sums it up well; "Octopuses, squids, cuttlefish and the chambered nautilus belong to class Cephalopoda, which means 'head foot'. Cephalopods are a class in the phylum Mollusca which also contains bivalves (scallops, oysters, clams), gastropods (snails, slugs, nudibranchs), scaphopods (tusk shells) and polyplacophorans (chitons)"2, however unlike their relatives, cephalopodsmove much faster, actively hunt their food, and seem to be quite intelligent.

Physiology

A cuttlefish has 8 arms, with two rows of suckers along each arm, and two feeding tentacles with at least two rows of suckers along each. The tentacles are tipped with a tentecular club, each covered with suckers while the 'shaft' of the tentacle is smooth. The tentacles and tentecular club act much the same as a chameleon's tongue; they shoot out to snare prey and bring it back to be eaten by a beak-like mouth and a wire brush like tongue called a radula. Cephalopods have three hearts, a ring shaped brain, blue, copper based blood, and have a lifespan between 6 months and 3 years.

Cuttlefish have amazing eyesight having 'w' shaped pupils which, according to cephalopod specialist Mark Norman "when closed, forms two separate pupil openings."3

They are also known for the amazing chromatophores, leucophores and iridophores that change the color of their skin (photos 3 and 4). At any time, half of their body may be one pattern, while the other is completely different pattern. The patterns aren't necessarily static either, they move, like animation on a TV screen; one pattern is referred to as 'passing clouds' because it seems to mimic the shadows of clouds passing overhead - although the pattern is also thought to mesmerize prey (see videos at www.DaisyHillCuttleFarm). These animations are thought to aid in communication, hunting and camouflage. To evade predators or hide from prey, they not only rely on their color-changing abilities but will also shape skin on their bodies into textured protrusions (Photo 5), expel ink from their bodies, and 'jet' rapidly away from danger.

Photo 3: 2 week old S. bandensis, about 1 inch long. Note the detail of the skin structure. Photo, Richard Ross

Photo 4: Adult S. bandensis mimicking the cyano covered tubing which it is hiding under. Photo, Richard Ross

For locomotion cuttlefish generally use a two-tiered approach: a fin that girds their mantle, as well as the jet propulsion of water pumped over the gills and through their funnel. This 'jetting' is often used when the animal is seriously threatened, and can move the cuttlefish surprisingly quickly. Some cuttlefish, like S. bandensis and Metasepia pfefferi (flamboyant cuttlefish), actually walk across the sand using their bottom two arms and two lobes on the back part of the bottom of the mantle.

One of the most well known features of the cuttle fish is the cuttle bone, which is used by pet owners to provide calcium for caged birds. This lighter-than-balsa-wood, gas filled, multi-chambered internal calcified 'shell' gives the cuttlefish its buoyancy control.

Cuttlefish can also produce copious amounts of ink if startled. It is thought that the ink acts as a smokescreen to allow the cuttlefish to escape predation. Some cuttlefish ink forms 'pseudomorphs', or blobs of ink that are thought to further aid in escape from predation by presenting the predator with multiple targets. The question of the toxicity of cuttlefish ink is still up in the air, although it is clear that some cephalopod ink is indeed toxic, but again, the major reason the ink is thought to be toxic is because it coats their gills, causing them to suffocate. This ink has been used by humans as, well, ink; the genus shares its name with ink - Sepia. The cuttlefish ink is also used as an ingredient in many 'snake oil' medicines that claim to cure everything from insomnia to menopause. Cuttlefish are also quite tasty, and prepared in every way possible, from raw to deep fried snack foods.

Hard to Keep?

Cuttlefish have traditionally been thought of as a difficult animal to keep. I don't think that is necessarily true - IF you can keep a reef tank (and understand the basics of cuttlefish care). If you have never kept a reef tank, I would strongly suggest keeping one before you start on cuttlefish - even if not all husbandry methods are transferable. Since the basics of keeping both coral and cuttlefish are similar, and since cultured corals are becoming so readily available, coral seems like a better creature to "learn on" than cuttlefish.

In my opinion, much of the reputation of being difficult to keep comes from cuttles being mistreated during collection and shipping: often housed together, the resultant fighting can cause injuries and infections, while stressed animals can ink in shipping bags causing them to suffocate.

If you can get your hands on a cuttle in good shape, I have found them to be pretty resilient and adaptable. Two cuttles I recently got from a local wholesaler were in good shape and were eating thawed frozen krill the second day I had them, and exhibiting 'begging' behavior on the third!

However, please remember that cuttlefish are short-lived animals (which has also bolstered the thought that they are difficult animals to keep), so get prepared for your little alien friend that greets you every time you walk into the room to be with you for l3 months or less. According to James Wood, "lifespan in cephalopods seems to be a function of two things, the water temperature that they live at and the size they mature at. Species that mature at a small size and live in warm water have the shortest lifespan."4

There are many ways for a cuttlefish to die. An injury from fighting can become infected or the injury itself can be terminal. Sometimes, a cuttlefish will be eating well and active one day, only to be floating lifeless the next morning. If you are able to keep a cuttlefish to the end of its natural lifespan, you may get to experience the animal going through senescence, which really means the process of getting old, but in cephalopods the process is downright gut wrenching. The onset of senescence is often marked by a clouding of the eyes. Since eyesight it central to a cuttlefish's hunting ability, such clouding can be disastrous. The ability to track and catch prey is impeded, with the animal's tentacles seeming to not function properly and an inability of the tentecular club to hold onto prey. Eventually, the animal can become lethargic, showing no interest at all in eating or even moving. To make it even more painful, senescence can last for days or months.

The death of your cuttlefish is awful and it is going to happen; be prepared.

Available species

There are essentially two species of cuttlefish that are 'available' to the aquarium trade - Sepia officinalis and Sepia bandensis.

Much has been written about S. officinalis because they are bred all over the world for different kinds of research - from neuron research to behavioral research. While S. officinalis are pretty simple to get a hold of if you are a researcher, or live in Europe, they are quite difficult to get in the US. What's even worse from a practical point of view, is they get big - 18 inches. It is recommended that the smallest aquarium for a single animal be at least 200 gallons. They are from 'cool' waters and like a water temp between 59 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit.

I believe that Sepia bandensis, on the other hand, are the perfect animal for the home aquarium because they are small: about 4 inches. Since S. bandensis is the species with which I have the most experience, they are the focus of this article. However, if you are interested in Sepia officinalis, please read this article by Colin Dunlop (http://www.tonmo.com/cephcare/cuttlefishcare.php), or this article by Dr. James Wood (http://is.dal.ca/%7Eceph/TCP/cuttle1.html).

There are many Sepia species that are similar to each other, and many may not have been identified yet, so proper identification can be very difficult. For instance, it is possible that the first cuttles I got were not S. bandensis, but I only came to this conclusion after raising bunches of cuttles that I am more sure are S. bandensis through observations.

Other species sometimes seen in the hobby are pharaoh cuttlefish, Sepia pharaonis, which are even less available than S. officinalis. I once had the honor of keeping a flamboyant cuttlefish, Metasepia pfefferi - but not enough is known about them to make me feel comfortable recommending them as pets, and there seem to be indications that their populations in the wild are in decline.

Getting a cuttlefish

Getting a cuttlefish, especially in the US, is currently difficult. There are no cuttles native to North America, so unlike our friends in the rest of the world, you can't just go and collect your own; you have to hope that your LFS will get one in stock. Still, there is hope.

There are other people, just as into cuttlefish as I am, working on breeding Sepia bandensis in the US and the UK. Last year Octopets.com offered captive raised Sepia officinalis for sale - and plan to again this year. Octopets.com is the only facility culturing octopus for the hobby in the US, and they also sell a variety of other marine animals. Recently, I have been working with Octopets.com to help them establish S. bandensis brood stock on a larger scale than what I am working with.

I am a huge fan of captive propagation in general, and think the benefits of captive-bred or captive-raised cuttlefish are massive - the animals are already acclimated to captive conditions, already eating available foods, and don't go through the stress of being collected or shipped from another continent; not to mention reducing the demands on wild populations.

Another option is to raise your animals from eggs; cuttlefish eggs, usually S. bandensis, show up in the hobby from time to time. They are usually added to orders as 'filler' and one wholesaler told me they feed them to fish at his facility! Raising baby cuttles from eggs has its own host of problems and benefits that will be addressed later in this article.

Setting Up for S. bandensis

S. bandensis don't get very big, 4 inches or less, and a single animal can easily be kept in smallish aquaria. They seem to be very reluctant to ink, they tend to become very personable very quickly and, unlike octopus, they don't try to escape from their aquarium. Whenever I walk into my cuttle room, they all swim to the front of their tanks to see if I will feed them. They really seem to be the perfect cephalopod for the home aquarium.

Below is a breakdown of what is needed to keep a single S. bandensis in a sumpless system. I am not going to go into very much detail because I am hoping that anyone who wants to keep a cuttlefish already has some basic experience in keeping saltwater tanks and understands the nitrogen cycle. If you don't, but are still interested in keeping a cuttlefish, I suggest you check out Reef.org's New Reefers Forum (http://reefs.org/phpBB2/viewforum.php?f=64 ).

- S. bandensis can be kept in tanks as small as a 20 gallon high, although a 30 gallon high is better for a single animal. They prefer to have a tall tank, and seem to like the feel of the height of the water above them. They can, of course, be kept in bigger tanks, but the bigger the tank the harder it might be to make sure a small cuttlefish sees its food.

- Any water pump, powerhead or filter intake should be covered with a filter sponge, or something similar, to keep the cuttlefish from being sucked into the filter or sucked against the intake.

- A protein skimmer is a must, not only for oxygenation and water cleanliness issues, but also to deal with ink events. A hang on back skimmer will work just fine - I like the Bak Pak with a wooden air stone added to the reaction chamber to produce more foam. I have also used the Remora Pro, but never really got much skimmate out of it, but some people swear by them. Any decent skimmer will do.

- A hang-on back - Preferably with a surface skimmer attachment to suck 'scum' off the top of the water. The mechanical filtration provided is helpful because cuttlefish are messy eaters and messy excreters. A HOB filter is also a good place to run carbon to help deal with inking events or other water quality issues. Make sure you change or rinse the filter media often. The HOB filter will also give you plenty of circulation for S. bandensis - provided you get the right sized filter for the right sized tank. I use Aquaclear 500's on 20 gallon high tanks. A canister filter will also work just as well.

- Extra water flow - If you need extra water flow, a power head will work just fine (but cover the intake with a filter sponge!). Air pumps are also very efficient at moving water, and make especially good water movement for baby cuttlefish.

- Heater - S. bandensis come from at least the Philippines, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea and seem to do just fine between 78 and 80 degrees.

- Chiller (if you need it). In the SF Bay area I have never needed one, but if I did need one I would use an IceProbe Micro Chiller DIY'd onto a hang on back filter. I doubt you would need one for this species. For S. officinalis you very well might want one.

- Water quality - Specific gravity should be around 1.025, pH 8.1-8.4, Ammonia, nitrite and nitrate as close to 0 as possible.

- Make sure that the tank has completely finished its nitrogen cycle and is ready for a high biological load before adding a cuttlefish.

- Lighting is not much of an issue as cuttles don't really need it. I use Lights of America fixtures5 from Home Depot or Costco to keep the macro algae growing. Some people have reported cuttles going blind from high intensity lighting, but I am not sure if I believe it. Cuttlefish eyesight tends to go as they reach senescence - the eyes cloud over and they find it hard to see their prey, and these are the symptoms that people have reported keeping cuttles under high intensity lighting. It is hard to tell if the timing of the eye problems is coincidence or caused by the lighting. Your lighting will also determine what corals, if any, you keep with the cuttle.

- Aquascaping - I like to create big arches so the cuttles have places to hide, but are still easy to find. I suggest going light on the live rock to make it easier to find the cuttlefish - remember they are masters of camouflage.

- A sand bed of 1/2 inch depth is fine. The cuttles will dig around in the sand, so a deep sand bed might be problematic.

- S. bandensis are often found among sea fans, but seem to do very well with hanging macro algae. You can hang your macros with a lettuce clip used to feed tangs and angels vegetable matter.

- Top off - over time the water in your tank will evaporate, and will need to be replaced. Note that the salt does NOT evaporate, so your top off water should be reverse osmosis water or reverse osmosis/deionized water heated to the temperature of the tank. How often you will need to top off your tank will depend on the rate of evaporation you experience.

- No copper! Copper will kill cuttlefish.

- Water changes - I recommend a 25 -50 percent water change once a month. The water should be reverse osmosis water or reverse osmosis/deionized water mixed with a good quality salt mix, heated and aerated to tank temperature for 24 hours before adding it to the tank.

Of course, a system with a sump would be fine as well. A sump is essentially another tank below the show tank, often kept inside the tank stand. Water drains from the show tank into the sump, and is then pumped back up into the show tank. Sumps do basically two things - they give your system a larger water volume which makes the system more stable and they give you a place to put equipment that may be unsightly, like your skimmer, heater or chiller. A 50 or 100 micron sock can also be added to the end of the tank drain for extra water filtration, but make sure to clean it at least once a week, if not more, so the detritus collecting in the sock don't break down and cause water quality issues.

Keeping groups of S. bandensis:

I have not experimented much with keeping groups of S. bandensis together. I have had so few animals, and I didn't want to risk losing them to possible injuries from fighting. It may very well be the case that keeping groups, especially groups raised together, of S. bandensis in the same aquarium turns out to be a great way to keep them. It may also turn out that the fear of fighting is overrated. I think that as long as they are given a large enough tank that they should be fine, but I have no ideas as to what constitutes 'large enough'. When the current babies I have are old enough, I plan on keeping a group of them in an undivided 100 gallon tank, so I should have more information in the near future.

Tank Mates for S. bandensis:

Most fish, shrimp and crabs that are smaller than the cuttle will eventually become food…they will even eat mantis shrimp. Larger animals may distress the cuttle. In short, I would NOT recommend having fish and cuttles in the same tank. Snails, however, are completely safe in my experience.

Any kind of non-aggressive coral should be fine with cuttlefish. Anything that tends to sting should be avoided. Mushrooms, colt corals, 'tree' corals, clove polyps and green star polyps are all good choices for a cuttle tank. SPS corals may not be good choices for lighting reasons and water quality issues.

Feeding S. bandensis

Cuttlefish are predators eating mostly crustaceans and fish. It seems that motion triggers their amazing hunting response, so lots of people want to feed them live foods. This can be problematic because live food can be expensive, and even though cuttles will eat fish, they really are crustacean eaters. The most widely available live crustation for food is the ghost shrimp, which is good for a snack, but may not be the best everyday food.

There are several options to feeding your cuttlefish. Variety is always a good idea, as it covers more nutritional bases and keep the cuttle mind more active.

- Live saltwater crabs/shrimp collected locally. This is a great, inexpensive food source if collected from a clean area. I live near the SF Bay, and crabs are easy to collect, but I am now worried about the pollution levels being problematic for the cuttlefish, so I don't use them as my primary food source. Also, remember not to feed crabs or shrimp that are bigger than the cuttle just because it is cool to watch the fight - prey has defensives and will often injure the predator. (Photo 6)

- Live saltwater fish collected locally: See above - but remember that Crustaceans make up the bulk of cuttle diets in the wild, so a fish-only diet is not best. If you are interested in seeing what different species of cuttlefish eat in the wild, please see Cephalopod Prey in the Wild (http://www.cephbase.dal.ca/preydb/preydb.cfm). Even though there is not a lot on S. bandensis, the information may be informative.

- Live saltwater crabs/shrimp or fish for a live bait shop: Great if you can find 'em, as long as they are collected from a clean area.

- Live saltwater fish from an LFS: Not the best option because this usually means damsels, which can be pretty aggressive and can even injure the cuttlefish - not to mention expensive. (Photo 7)

- Live saltwater shrimp/crabs from the LFS: Great if you can afford them. They will almost always be expensive, but can be a good option in an emergency. Hermit crabs, like clean up crew hermits, aren't the best idea because they are so small and can disappear into their shells - and the cuttlefish may ignore them completely.

- Live freshwater crabs/shrimp: It is questionable if freshwater animals make good food source for saltwater animals - there may be missing nutrients or may have incompatible amino acids. Otherwise, ghost shrimp are eaten with gusto by cuttlefish, as are small fiddler crabs or very small crawfish. The big drawback is if the cuttle doesn't eat the animal, you now have a freshwater animal in a saltwater tank . . . which may die and pollute the water

- Live freshwater fish: Guppies seem to be ok, but goldfish seem to cause indefinable problems. The big worry is that these animals are treated with copper or other chemicals that can be detrimental/disastrous to the health of the cuttlefish.

- Frozen Krill, fish, or other (but not cooked!): As a general staple, frozen krill from the LFS or fresh frozen, rinsed shrimp/non oily fish from your local grocery store are great. Make sure you thaw the food completely, and it is a good idea to supplement once in a while with live food. Please note that weaning your cuttles onto frozen food can be a challenge. The trick is to make the dead food look alive via a clear feeding stick or by having it 'blow' around in the current. Two wild-caught cuttles I currently have took to frozen food almost immediately with almost no work on my part, while other cuttles I have had would never even look at it.

- Ordering live food from the internet: Great but expensive due to overnight shipping costs, and you will need to set up a separate tank to keep them alive. Check out TOMNO.com.

I suggest feeding cuttlefish at least once a day, and promptly remove any uneaten food from the aquarium. They will eat a lot more than once a day, but it does seem like it is possible to over feed them. Their metabolism is very fast, so I wouldn't suggest not feeding them for more than a couple of days in a row. Cuttlefish floating near the surface may be a sign of starvation, so be on the lookout for this behavior.

Rearing S. Bandensis eggs

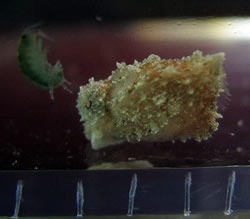

S. Bandensis eggs look like a cluster of 8-40 grapes, are dark purple to black in color (the outside of the egg is partially made of ink) and generally stay attached to each other even after they are removed from whatever they were attached to by the female cuttlefish. The eggs are pointy when laid, but as they mature, they swell, become round and eventually grow so transparent that you can watch the baby swim around inside. After 2-3 weeks, the baby cuttlefish emerge from the eggs ready to meet the world. Sometimes a yolk sack is still attached, however this is generally considered to be an effect of a premature hatching. Though tiny, they are perfect replicas of their parents and begin color changing almost immediately (and even while still in the egg!) (Photos 8 and 9)

The cuttlefish are born as small as 4 mm (Photo 10), but grow quickly, up to 1 cm in one month! I keep newly hatched S. Bandensis in net breeders so I can keep track of them and make sure they are all eating (I turn the net of the net breeder inside out so the extra material is on the outside of the net breeder so the babies don't get caught in it). If the babies are kept in the main tank, they can easily get lost or sucked into a filter. I am also experimenting with keeping baby cuttlefish in display 'cubes' like you see in aquarium stores. I often keep up to 5 individuals in the same net breeder for several months, or until I begin to see fighting displays (Photo 11). Then, I move them into sectioned off areas of the 100 gallon tank. I have tried keeping groups together for mating and tried keeping individual animals apart except for mating, and have had equal results in both cases, but will use a larger space for groups in the future.

Photo 10: Baby S. bandensis. Marks

at the bottom of the frame are 1/8 inch apart.

Photo, Richard

Ross

Photo 11: Video frame of

2 male S.

bandensis intimidating each other with

visual displays.

Photo, Richard Ross

If you have a cuttlefish that lays eggs, leave them where they are until they start to inflate. Then you can carefully remove them from whatever they have been laid on by removing the 'stalk' of the bunch of grapes from its point of attachment and move the eggs to a net breeder or other hatching container (avoid moving them close to hatching, because it can be stressful) (Photos 12 and 13). It would be even safer for the eggs if you were able to move them by moving whatever it is that they are attached to, or you could suspend the eggs in the middle of the water column via monofilament or bent rigid airline tubing. Keep a gentle water flow over the eggs and remove any eggs that fail to mature. Make sure to cover any filter/pump intake with a filter sponge, or simply use an airpump for water motion.

Eggs come with their own set of pros and cons. The pros are big - the eggs ship well and take up little space, and allow you to know the exact age of your cuttles. However, the major con is massive - feeding the babies. Baby S. bandensis may not eat for 2 or 3 days after hatching, but once they get started, they eat an amazing amount of food, and the food has to be the right size. Live mysid shrimp make the perfect food, but you need lots of them, and to make matters worse, mysids are cannibalistic so you have to keep them in a large enough container and feed them enough so they won't eat each other.

If you are lucky enough to be able to collect your own, or live near some place that cultures them and will sell them to you, or decide to (shudder) culture your own, you win. Otherwise you will need to have them shipped to you overnight and incur those expenses. When I shipped in live food, I was very happy with www.mysid-shrimp.com, a division of Reed Mariculture.

If you live near the coast, you can also collect amphipods (Gammarus spp) for baby cuttlefish food, which is actually pretty easy. I prefer to go to a gravelly area that gets exposed at low tide, find a rock about the size of a dinner plate, flip it over and scoop the revealed gravel into a bucket with some tank water. When I get home, I drop a net in the bucket. The pods tend to cling to it and voila… easy baby feeding. (Photo 14 and 15)

Photo 14: Three week old baby S. bandensis and Gammarus spp amphipod. Marks at the bottom of the frame are 1/8 inch apart. Photo, Richard Ross

UK S. bandensis keeper Mike Irving collects mysid shrimp for his baby cuttlefish: "In coastal areas you may find that you have mysids living. Usually they are more abundant in tidal areas, or where fresh water run-off meets salt water. Mysids live at the sand surface, so in order to collect them, you should take a fine net (sized so that is will let silt through but not the mysids) and run it along the surface of the sand/sediment. As you net disturbs the mysids and sweeps through the water, you will catch the mysids.

A word of warning - when you collect mysids yourself, first make sure that the water is unpolluted (however the presence of them can sometimes indicate so, and that you do not collect too many. When transporting them from coast to home, if you over collect for your transportation receptacle (bucket!) they mysids use up oxygen fast, and you can end up with a bunch of dead shrimp. Collect light and aerate with a tube if you can - even better buy a battery operated air pump."

Baby fish can also be an option (octopets.com sells baby saltwater guppies). Some people will use enriched small brine shrimp but only in a pinch - it is thought that long term, brine are not an adequate cuttlefish food.

Another thing to try is to wean them onto frozen mysids. Put cuttlefish in a small tank, cube or net breeder with enough circulation to keep the thawed mysids moving and after a few days the babies should start eating them.

Warning: It is not known how well S. bandensis can do with a diet of only saltwater guppies, enriched brine shrimp, or frozen mysids. A varied diet of other live foods seems to give the best chance of survival.

Breeding S. bandensis

I have had limited success breeding S. bandensis - mainly through trying to keep breeding groups or pairs in hobby sized tanks. I get lots of mating, but have lost the parents before egg laying for reasons I believe may include fighting due to limited space, separated cuttles injuring themselves trying to get to each other through dividers, or slow poisoning via live foods collected from the SF bay.

Cuttlefish breed by coupling head to head, and the male packet of sperm called a spermatophore, is deposited into a pouch in the female's mantle (Photo 16) The mating can last from 10 seconds to many minutes, and in some species, males will use their funnel to flush other male's sperm out the females pouch.6 Femalescan lay several clutches of eggs, and can live for months after egg laying.

Even though cuttlefish can tell each others sex on sight, it is very difficult for humans to accurately sex them if you don't actually see them breeding. In general, S. bandensis males tend to adopt high contrast black and white patterns when faced with another male while females tend to keep the more relaxed mottled colors that a resting cuttlefish adopts. However, males sometimes display like females and females sometimes display like males, so introducing S. bandensis that don't know each other should be done with care.

The method of introduction and sexing that I am using developed with much help from Chris Maupin. So far, while not perfect, it seems to be effective. I built movable partitions in a 100 gallon tank, each with a removable door that can be either be transparent or opaque.(Photo 17) To try to sex the cuttles, I put in the transparent door to see how they react to each other. Hopefully, those reactions will allow me to determine the sex of the animals. James Wood suggests holding a mirror up to the tank, but I haven't tried this method of sexing yet.

When I think I have a male and a female, I remove the door and watch as the two cuttles face off. Males and females will mate pretty much immediately, while two males will display and fight (Photo 11). After breeding, I separate the two to prevent fighting. If the pair ends up being two males, I separate them as quickly as possible.

The first pair I successfully bred produced one clutch of eggs using this method. The next cuttles I raised were all male. The third attempt seemed successful, and the pair mated like crazy, when disaster struck. The two lovesick cuttles were so eager to get some "unsupervised" time together, that they attempted to mate through the mesh of the tank dividers. Both animals were injured, and died shortly thereafter.

Photo 19: Rear view of 3 week old S. bandensis eating an amphipod. Marks at the bottom of the frame are 1/8 inch apart. Photo, Richard Ross

Photo 20: 3 week old baby S. bandensis. Marks at the bottom of the frame are 1/8 inch apart. Photo, Richard Ross

I have also kept groups of cuttles together to see if they would pair off or mate without intervention, but have had little success, mostly due to apparent fighting. It is probable that the space I gave these groups was simply too small.

When the babies I currently have are old enough, I will modify my procedure. The modifications I'm considering are: using different dividers, leaving an empty space between divided cuttles to prevent them trying to reach each other, and using a much larger tank/tub as an environment for small group to live in. I suspect that S. bandensis would be easy to breed with a group of 10 or so as long as they were in a 300 gallon tub with plenty of macro algae for hiding.

Conclusion

Cuttlefish are fantastic animals, and I am still amazed that I have them in my home. I hope that as more people begin to keep and breed them that they will become a captive bred staple in the aquarium hobby. I also hope that you have found this article helpful, and that your interest in keeping and breeding cuttlefish has grown. If you have any information on keeping or breeding Sepia bandensis, or if you have found any errors in this article, please contact me because to make captive bred bandensis readily available we need to pool our information.

Acknowledgments

My efforts with Sepia bandensis would not have been possible without the generous help of Bob Mendelsohn, Chris Maupin, Colin Dunlop, Mike Irving, Dr, James Wood, both the Reefs.org and TONMO online communities and the information compiled by Dr. James Wood on The Cephalapod Page and Cephbase. I also need to thank my wife Libby for allowing the absurdity of attempting to breed cuttlefish in a house and for her immeasurable help in writing this article.

External Links

- www.DaisyHillCuttleFarm.com

- The Cephalopod Page - http://www.thecephalopodpage.org

- The Octopus News Magazine Online - www.TONMO.com

- CephBase - http://www.cephbase.utmb.edu/

- Mike Irvings www.CephsUK.co.uk

- www.Octopets.com (now defunct)

- Lights of America Fixtures - http://www.lightsofamerica.com/floods.htm

References

- Norman, Mark (2000), 'Cephalopods a world guide', ConchBooks PP 1-92

- http://www.cephbase.utmb.edu/TCP/faq/TCPfaq2b.cfm?ID=4

- http://is.dal.ca/~ceph/TCP/index.html

- Norman, Mark (2000), 'Cephalopods a world guide'. ConchBooks : pp.82

- Private correspondence referring to the following paper: Wood J.B. and R.K. O'Dor (2000). Do larger cephalopods live longer? Effects of temperature and phylogeny on interspecific comparisons of age and size at maturity. Marine Biology. 136 (1) : pp.91

- Norman, Mark (2000), 'Cephalopods a world guide'. ConchBooks : pp.42